This timeline is an overview of significant events tied to the establishment of The Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. Weaving together a combination of institutional achievements, local Los Angeles history, and significant national cultural and political events that shaped culture during the 1950’s and early 1960’s. Although this timeline begins with the critical donation of Olive Hill to the city by Aline Barnsdall in 1927, the timeline focuses on the 1950’s when the gallery was officially established. This timeline aims to illustrate how these events informed the stewardship of LAMAG.

By Hugo Cervantes

The establishment of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery (LAMAG) is a unique story of Angelenos forging a vision of civic arts. The gallery and its sibling institutions: Barnsdall Arts Center, Junior Arts Center, Barnsdall Gallery Theater, and the Hollyhock House – recognized today as an UNESCO World Heritage Site, constitute Barnsdall Art Park, an arts campus operated by the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA). These five cultural institutions are a result of years of advocacy from Angeleno artists, cultural workers, and citizens committed to realizing the full potential of public arts for all. The efforts of establishing all five institutions vary and are specific to the institutions own history yet all share a common plight of advocating for a city-led public arts program. Preliminary struggles driven by a combination of national anxieties and a resistance to the introduction of new ideas define LAMAG’s early years in conversation with how civic leaders addressed and adapted to these challenges contribute to the institution’s perspective. It is their efforts that laid a meaningful foundation for future generations to build upon and complicate in a generative way to showcase the life-affirming and life-changing qualities of the arts.

Barnsdall Park is indebted to Aline Barnsdall, oil heiress and philanthropist, who donated the property, what was then a 36 acre functioning olive grove in East Hollywood called Olive Hill. Of her 36 acres, Aline donated 11.56 acres, including her residence, the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Hollyhock House, to the city in 1927

(1). Barnsdall, a champion of the arts with an affinity for theater and performance, envisioned Olive Hill as an arts oasis delineated by her proviso that the land be used solely for art purposes (2).

Reflecting on her gift of Olive hill, Barnsdall said, “I thought of my father, of the happiness of children and young people with Olive Hill as a place to work and play, a background for their dreams and memories, and my reluctance to see a building and landscaping of great beauty destroyed, and now of my triumphal joy at seeing it saved” (3). Over the years, there has been a continuous effort to adapt the park to the ever-changing needs of the city’s diverse communities to bring us to today, where under the stewardship of the DCA, Barnsdall Park embodies her vision for a public park dedicated to the arts. Specific to the story of Barnsdall Park is the creation of a city-led art gallery—The Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery—opening as a temporary space in 1954, but was formally established as a permanent program in 1957, which leads to a more philosophical question: What role should local governments play in the development of arts programming for its residents and arts community? It is a question that foregrounds the formation of the gallery, outlines its civic responsibilities, and shapes its history. These are questions early civic leaders, artists, and Angelenos contended with since the gallery’s inception.

These questions arose from a public who desired a new framework for the arts, one that allowed space for experimentation and presentation of new ideas rather than the repeated celebration of old masters. These wealthy private clubs had a preference for the figurative and pastoral, rejecting the expressionist styles of art percolating in the early twentieth century that would later dominate the international arts circuit of world fairs and biennials. Critical to these private art clubs was their control over which type of arts were celebrated and deemed important, and who was allowed to view and participate in the arts. For the private art clubs, they viewed art as a method to legitimize their worldview and to affirm the status quo rather than question or challenge it. However, by the end of World War II the United States had created a subset of programs from 1933’s New Deal and 1944’s G.I. Bill that encouraged a younger generation to educate themselves and hone in on their artistic sensibilities. By the time the 1950’s rolled around the nation’s political and cultural landscape ripened these ideological debates expressed in the arts as modern art versus “traditional art,” and who would be in control over cultural institutions and the dissemination of these news ideas, and of culture at-large in the United States.

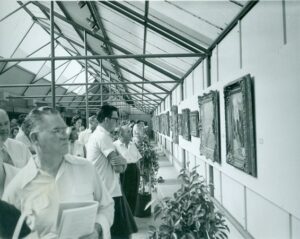

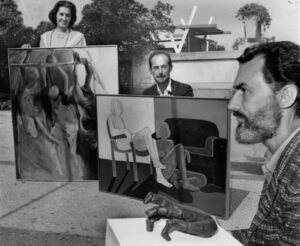

LAMAG opened its doors in June of 1954 with 60 Years of Living Architecture, a Frank Lloyd Wright retrospective (4), in an exhibition hall nicknamed “The Shed” (5) designed by Wright’s studio, with structural engineering support by Morris S. Pynoos and Eugene Birnbaum (6). This exhibition hall was connected to the Hollyhock House garage and measured 216 feet long and 20 feet wide, with individual artwork display bays adapted from the House’s animal pens, as well as a lecture room. Originally designed for Wright’s retrospective, the exhibition hall was not an ideal venue to display artworks as the hall was open to the elements via slits throughout the roof and the base walls left open for ventilation (7). Although, Ross did make adjustments to the exhibition hall to meet certain standards and to be able to hold exhibitions for a length of time. Despite the flaws of this exhibition hall, LAMAG would continue to organize exhibitions in the “The Shed” from 1954 to 1968 (8) hosting a combination of old masters, modern, and emerging artist exhibitions. Some exhibitions of note are: Van Gogh (1957), Hammer Brothers Collection (1958), Salvador Dali Apocalypse (1964), Norman Rockwell (1966), and the annual All-City Outdoor Arts Festivals (ACOAF.)

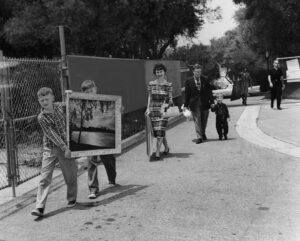

While utilizing “The Shed” for exhibitions, the forward thinking Municipal Arts Department (now the Department of Cultural Affairs), General Manager and LAMAG Director, Kenneth Ross, considered how the Gallery could maximize its reach to various Angeleno communities. Familiar with Los Angeles sprawl and how it structured and informed the city’s social activity, Ross applied a decentralized approach to civic arts programming, most effectively exemplified in the ACOAF. The ACOAF were city-wide open call exhibitions granting professional and non-professional artists to exhibit their artwork side-by-side at various public parks throughout the city. Ross conceived of the ACOAF as a response to the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art’s version of the open call, Artists of Los Angeles and Vicinity held in Exposition Park, where many artists submitted their work but were denied participation which, for Ross, was misaligned with a public museum’s goal. This prompted him to consider, what if every artwork submitted to an open call could be shown (9)? The ACOAF was born to serve and celebrate Angeleno artists of all types and the joy of making art rather than instrumenting art to establish hierarchies. Ross’s concern of accessibility extended to underserved communities such as African-American and Latinx communities in South Angeles. For the inaugural ACOAF in 1950 he hired the artist Beulah Woodard (10) to lead the festival at South Park on 51st Street and Avalon Boulevard. Its success rolled into continued arts programming at South Park after the ACOAF.

The ACOAF would become a defining exhibition that would shape LAMAG and the Municipal Art Department. LAMAG’s ACOAF curatorial vision for a city-wide exhibit celebrating artists of all types was a radical idea in an era where private art clubs supervised and defined ideas of art. The ACOAF celebrated the spirit of art-making above all and effectively flattened a hierarchy of value—no one artist or type of art deemed more esteemed over the other—a position that was furiously contested at the time. Another distinguishing element was its city-wide approach that included many Los Angeles neighborhoods (South, East, North, West L.A.) in a city where cultural institutions then were often concentrated in a general area of the city. Ross’s city-wide ACOAF (11) ensured participation from all parts of the city.

The popularity and success of the ACOAF and other programs like 1952’s Henri Matisse exhibition, along with The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), supported Ross’s advocacy for the creation of a proper Municipal Art Gallery in 1954. However, its triumphs also invited criticisms from local private art clubs and City Council Members concerned with the favoring of one style of art over the other – “traditional” styles that favored realism over experimental and expressionistic modernist styles. Backgrounding the success of the first three ACOAF (1950-1953) was a dire moment in American history with a critical peak of the Cold War producing a second wave of red scare, and the start of the Korean War in 1950. The combination of these national events created a paranoid landscape where politicians and institutions were quick to identify potential traces of communist influence to be exterminated either by firing or blacklisting. In other words, red-baiting became a common intimidation tactic to antagonize individuals in the public and private sphere.

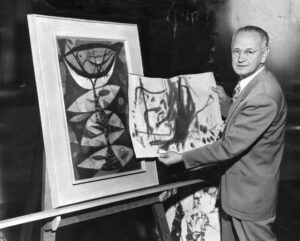

The second ACOAF opened on October 1951 at the Greek Theater in Griffith Park and at other public parks, and included over 180 exhibits in total chosen from 1,800 submissions (12). The city-wide exhibition was accused of exhibiting artworks expressing “communist infiltration” (13) by the City of L.A.’s Building and Safety Committee, led by City Councilman Harold Harby. He requested for Ross and selected participating ACOAF artists like Rex Brant, Bernard Rosenthal (14), and Gerald Campbell to city chambers on October 24, 1951. The public hearing was intense. Councilman Harby questioned the artists, focusing on the intentions and meanings of specific artworks like Brant’s Surge of the Sea, a painting of a sailboat who was said to incorporate a hammer and sickle on the sail, Rosenthal’s sculpture Crucifixion deemed sacrilegious for an abstract depiction of Christ on the cross, and Gerald Campbell’s Landscape, an abstract illustration of a landscape, that all expressed, to Harby, communist ideals. The intensity of the hearings prompted a second round on October 31st, 1951.

This time in response to the Building and Safety Committee, Ross submitted “The Greek Papers,” a collection of documents asking the city council to rescind its accusation of “communist infiltration” in the interest of a constructive civic arts program signed by artists, businessman, and professionals (15).“A Statement of Modern Art,” a joint statement by MoMA, The Whitney Museum, and The Institute of Contemporary Art Boston issued in March 1950 critiquing government censorship of modern art reads, “We believe that it is not a museum’s function to try to control the course of art or to tell the artist what [s]he shall or not do; or to impose our tastes dogmatically upon the public. A museum’s proper function, in our opinion, is to survey what artists are doing as objectively as possible, and to present their works to the public as impartially as is consistent with those standards of quality which the museum must try to maintain” (16). Ross’s supporting documents advocated for his belief for the Municipal Art Department to be free of government censorship. The spectacle of the public hearing for Ross was interrupting Los Angeles’ potential of becoming a respected art capital. He states in the public hearing, “Many thoughtless and unnecessary things have been said…, some spokesmen not realizing that the words with which they describe a work reveal at once their own lack of knowledge. These statements … are going to be repeated nationally and unfortunately will not only make those who utter them seem ridiculous, but will make the city itself the laughing stock of rival cities” (17).

After long and tense conversations between City Council members, Municipal Art Department representatives, and Mayor Fletcher Bowron, the hearings finally came to a conclusion. The Building and Safety Committee submitted their report to the City Council expressing their final comments, “[they] did not believe that any individual artist at this exhibition was communist;… [they] were equally firm in the belief that [modernists] were being unconsciously used as tools of the Kremlin in this very effective propaganda field” (18). They requested for Ross to submit his annual budgets for the Municipal Art Department to the City Council for review and for future LAMAG exhibitions to be split into two categories: modern and traditional, with equal funding. This request would be later expanded in a motion lead by Councilman Ernst Debs and Edward Roybal, where they encouraged the Municipal Art Department to “investigate the advantages of the multiple jury and exhibit system, the no-jury system and all other methods current in common practice with an eye towards realizing the wildest possible democratic representation in civic art competitions” – a recommendation that would shape much of LAMAG’s future exhibition history still prominent today (19).

This drastically impacted LAMAG and the Municipal Art Department as it gave away its creative autonomy to be monitored by City Council, shadowing Ross’s forward thinking vision of a decentralized civic arts program. As a result the State of California incorporated the Municipal Art Patrons as a private nonprofit foundation and a funding source for the Municipal Art Department. LAMAG continued with ambitious exhibitions although it was restricted financially. However, Ross’s background and experiences at the short-lived Modern Institute of Art in Beverly Hills, professorship at the University of Southern California, and Director of the Pasadena Art Institute, bestowed him a wealthy network of donors like architect Paul R. Williams and Howard Ahmanson, Chairman of the Board of Home Savings and Loan Association. Ahmanson in particular was critical to the success of the ACOAF which, beginning in 1954 (after all of the public hearings culminated), provided funds for the exhibition, cash award, and often purchased artworks from the exhibition (20). This funding enabled the support of emerging artists of the 1950s and ‘60s like Sister Mary Corita Kent (1958), Charles White (1968), and David Hammons (1969).

The first ten years (1954-1964) of LAMAG illustrates a high-spirited portrait of civic leaders and cultural workers wrestling to define the role for local government involvement in the arts. Despite the challenges LAMAG faced in its early years, the decade is better remembered as a time of introducing ambitious and, at times, challenging ideas to Angelenos. These challenges are a part of a process of making new ideas like a city funded arts program irresistible and enticing for further consideration, support, and participation. LAMAG was able to organize and partner with a series of leading, often east coast, museums like MoMA, demonstrating a commitment to bring high caliber exhibitions to Angelenos. Although LAMAG faced some tough beginning years, the gallery was able to champion modern and contemporary art in a time when Los Angeles was building it’s cultural infrastructure like museums and galleries, on its way to becoming an international arts capital.

A distinguishing feature of LAMAG is its contributions to a system of art centers managed by the Department of Cultural Affairs, an arrangement unique to Los Angeles among municipal arts agencies, comparable to, for example, the University of California campuses, spread out throughout the state, that compliments the decentralized nature of Los Angeles. Its decentralized and inclusive approach laid an important foundation for artist communities and cultural workers to build upon in later years. Ross speaking to these principles said, “The artistic policy of the arts department can be stated in very simple terms: Los Angeles is a city of heterogeneous population and taste. This heterogeneity is part of its richness and is the fertile soil in which, through understanding, tolerance, and objectivity, a mature and significant art can flourish. So long as there is a broad base of expression in the city’s artistic program… a bigoted insistence on uniformity should not be made by anyone else in the community.” His understanding of the necessity of cultural and ideological diversity in Los Angeles as an indicator of a community’s strength exemplifies a deep understanding of what the arts can offer us– meaning, common ground, entry points to new and old ideas, and collective study. It’s a sentiment that grew and gained confidence at LAMAG in the later decades of the 1970s and 1980s. LAMAG’s early advocacy and championship for contemporary art predates local contemporary art museums like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), established in 1961, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), established in 1979, and The Hammer Museum, established in 1990.

For an institution that predates Los Angeles’ leading contemporary art museums LAMAG does not share a similar trajectory. In later decades the gallery trailed off into a middle ground balancing a community-arts and arts education curriculum while scheduling a combination of in-house curated exhibitions and hosting traveling exhibitions, and later demonstrating an emphasis on Los Angeles artists. While it’s important to note the gallery does not hold a collection, the city of Los Angeles does. Perhaps, this difference can offer one explanation for the gallery’s unique trajectory and to suggest further understanding on how municipal governance guides the gallery. The 1950’s at LAMAG might be marked by ideological and financial opposition but it is defined by how its leaders were able to overcome those challenges demonstrating the significance and importance of a city-led arts program. On a ground level, the establishment of the gallery developed a dynamic network of artists, curators, directors, art collectors, and other types of cultural workers, where they were able to meet, work together, and at times develop meaningful partnerships and friendships that would influenced Los Angeles art history. It is interesting to entertain the possibility of it if it wasn’t for the contested validity of Kenneth Ross’s All City Outdoor Art Festival’s by City Council that perhaps, Edward Kienholz would’ve never met Walter and Shirley Hopps who worked on the presentation of 6th iteration of the ACOAF and would not go on to open the infamous Ferus Gallery in 1957. Or on an institutional level, to consider how the preliminary efforts of establishing LAMAG would offer a template for future Department of Cultural Affairs facilities to be established like the Watts Arts Towers, which shares a similar yet different story to Aline Barnsdall’s donation of Olive Hill to the city.

If LAMAG’s first ten years are methodical, strategic, and a bit restrained, testing the boundaries of what’s possible in it’s municipal parameters, then in following decades the gallery explodes (within-reason). Taking advantage of the social movements of the 70’s and 80’s ushering in the energy of artists from the Black Arts Movement like in the exhibition, West Coast ’74: The Black Image. And taking an interest in advances of new technology in film and video and how artists were welding them like in the 1969 exhibition, The Film and Modern Art, made possible by The Constitutional Rights Foundation. These later exhibitions and possibilities originate from Aline Barnsdall’s feverish dream towards a public park in Los Angeles devoted exclusively to the arts. It is a dream extended by the great leadership of Department of Cultural Affairs General Manager, Kenneth Ross, his staff, countless city employees, artists and their communities, who understood the generational impact of establishing a city-led arts program, and how that could support Los Angeles to become an international arts capital. Barnsdall Art Park today operates with this founding mission in mind and continues to steward the park using the arts as a conduit to create meaningful points of connection and as a site to hold difficult conversations and expressions of new and radical ideas that reflect the experiences of Angelenos and beyond.

“Aline Barnsdall and Alfred Barr Poster Exhibitions, 1927 – 1937.” Socalarchhistory.blogspot.com, May 5, 2019.

“Art: Tumult in Los Angeles” Times Magazine online. November 5, 1951.

Carby, Hazel V., Getty Foundation, Hammer Museum, and Pacific Standard Time (Exhibition). 2011. Now Dig This! : Art & Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980. Edited by Kellie Jones. [First edition]. Los Angeles, Munich, New York: Hammer Museum : University of California ; DelMonico Books/Prestel.

“Edward Kienholz: The Story of an Artist.” Youtube.com/LaLouver. October 23, 2019.

Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, Sarah Schrank, and Sue Bell Yank, “Soc(i)al (Sept. 18, 2012)” KCET Digital, Soundcloud.com, May 31, 2024.

Fergeson, Cecil. “Civic Virtue: The Impact of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and the Watts Towers Arts Center: Oral History Interviews.” Tompkins Rivas, Pilar. Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, May 20, 2010.

Friedman, Alice t. 2009. Women and the Making of the Modern House: A Social and Architectural History. New York: Harry n. Abrams.

Hackman, William R. 2015. Out of Sight : The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties. New York: Other Press.

Herr, Jeffrey, and Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. 2005. Aline Barnsdall’s Olive Hill Project : Frank Lloyd Wright Sketches and Drawings, Edmund Teske Photographs. 1st ed. Los Angeles: Municipal Art Gallery, City of Los Angeles Dept. of Cultural Affairs.

Jones, Kellie. 2017. South of Pico : African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s. Durham: Duke University Press.

Karasick, Norman M., and Dorothy K. Karasick. 1993. The Oilman’s Daughter : A Biography of Aline Barnsdall. Encino, Calif.: Charleston Pub.

Kazor Ernst, Virginia. “Civic Virtue: The Impact of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and the Watts Towers Arts Center: Oral History Interviews.” Tompkins Rivas, Pilar. Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, September 29, 2010.

Kirschke, Amy Helene. 2014. Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

“Large Art Center City’s Greatest Lack,” LA Times, newspapers.com, August 23, 1953.

Masters, Nathan. “When East Hollywood’s Barnsdall Art Park Was an Olive Orchard.” September 15, 2014.

Meares, Hadley. “Barnsdall Art Park: Lofty Ambition Amongst The Olive Leaves.” October 24, 2014.

Merrell, J., Eric. “California Art Club in Search of a New Home: The Hollyhock Years, 1927 – 1942.” Winter, 2010.

Merrell, J., Eric. “The Birth of the California Art Club: Its Founding and First Annual Exhibition.” Summer, 2009.

Mizota, Sharon. “PST A to Z: ‘Civic Virtue’ at LA Municipal Art Gallery and Watts Tower Arts Center.” January 25, 2012.

Moure, Nancy. “The Struggle for a Los Angeles Art Museum, 1890-1940.” Southern California Quarterly 74, no. 3 (1992): 247–75.

Schrank, Sarah. 2009. Art and the City : Civic Imagination and Cultural Authority in Los Angeles. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Schrank, Sarah. “The Art of the City: Modernism, Censorship, and the Emergence of Los Angeles’s Postwar Art Scene.” American Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2004): 663–91.

Smith, Kathryn. 2006. Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock House and Olive Hill : Buildings and Projects for Aline Barnsdall. Santa Monica, CA: Hennessey & Ingalls.

Starrels Ianco, Josine. “Civic Virtue: The Impact of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and the Watts Towers Arts Center: Oral History Interviews.” Tompkins Rivas, Pilar. Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, April 16-18, 2010.

The Institute of Contemporary Art: Boston, The Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, “A Statement on Modern Art,” 1950.

Tompkins Rivas, Pilar. Los Angeles, California. Cultural Affairs Department, and Pacific Standard Time. Civic virtue: the impact of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and the Watts Towers Arts Center. Los Angeles, CA: City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, 2011.

Waldie, D.J. “Shock of the New: Los Angeles vs. Modernism.” PBSsocal.org, 21, July 2016.

Yank, Sue, B. “Is L.A. the Creative or Anti-Creative City?” pbssocal.org. May, 2024.

LAMAG Exhibition History

1960

Drawing and Sculpting Biennial & Australia Art, January 26 – February 21, 1960

Barnsdall Arts and Crafts, March 3 – March 12, 1960

Jamison Collection, March 22 – April 17, 1960

Sheridan Collection & Watercolor Society, April 26 – May 15, 1960

8th All City Outdoor Art Festival, June 24 – June 26, 1960

Sculpture of Negro Africa, July 12 – August 1, 1960

Form Givers at Mid-Century, August 16 – September 11, 1960

Crafts/Designers, September 27 – October 16, 1960

Christmas from Many Lands, December 8 – December 18, 1960

1961

Aldrich Collection, January 5 – January 29, 1961

Lebrun/California Etchers, February 7 – March 5, 1961

Cross Sections, ‘61/S.F./L.A. March 14 – April 2, 1961

Hollywood Celebrities Show April 25 – May 21, 1961

Image Retained & Indian Art May 30 – June 25, 1961

All City Outdoor Art Festival July 7 – July 9, 1961

Arts of Denmark September 27 – October 29, 1961

Barnsdall Arts and Crafts November 11 – November 26, 1961

Christmas from Many Lands December 7 – December 17, 1961

1962

Japanese Prints of Frank Lloyd Wright, January 9 – February 4, 1962

Hans Burkhardt & American Images, February 15 – March 3, 1962

Eskimo Art & North West Coast Indian, March 20 – April 15, 1962

Business Men’s Collection Art March, 27 – April 24, 1972

All City Outdoor Art Festival June, 15 – June 17, 1962

Garbisch Collection American Art, June 28 – July 29, 1962

Hallmark Collection, August 14 – September 9, 1962

Barnsdall Arts and Crafts, September 22 – September 30, 1962

And Now the Children October 9 – October 28, 1962

Century Drawings from MOMA November 8 – November 28, 1962

Christmas from Many Lands December 11 – December 21, 1962

1963

Pacific Coast Invitational, January 9 – February 3, 1963

Three for the Show February, 12 – March 10, 1963

Fechin & Photography in Fine Arts, March 19 – April 14, 1963

Phelan Awards, April 23 – May 17, 1963

th All City Outdoor Art Festival, July 13 – July 21, 1963

Dolls: Past and Present, July 30 – August 25, 1963

Iqbal Geoffrey, September 5 – September 29, 1963

Barnsdall Arts and Crafts, October 12 – October 27, 1963

Henry Moore, November 8 – December 1, 1963

Christmas from Many Lands, December 13 – December 21, 1963

1964

Mother and Child in Modern Art, January 15 – February 2, 1964

Arms & Armor of Ancient Japan, February 19 – March 22, 1964

Palette and Camera, April 18 – May 3, 1964

Belgian Painting, May 12 – June 7, 1964

All City Outdoor Art Festival, June 20 – June 28, 1964

Painting of the Year, July 10 – August 2, 1964

Ansel Adams’ Eloquent Light, August 18 – September 13, 1964

Salvador Dali & Apocalypse, November 20 – December 20, 1964

Please note our exhibition history is incomplete.