The election of President Obama in 2008 and re-election in 2012 marked the emergence of a new period in race relations and identity politics in the United States. One in which significant advancements underscore deeper, more persistent ruptures in the skin that binds us as Americans. President Obama, from a multiracial family, represented the most potent and singular figure for the progress made by the civil rights movement, multiculturalism, and identity politics from the previous decades. Some even argued that his election marked the moment of post-racism in the country’s history. And yet, since election, numerous racialized incidents have occurred that tell a different story. The exhibition SKIN brings thirty-six artists whose work is timely and engaged in many ways with these broader debates. The gallery acts as a discursive space where these disparate conversations can have a platform, and where further productive work and reflection on these topics can proceed.

These incidents include the recent high profile cases of police violence in New York, Ferguson, Baltimore and elsewhere that have brought to light racial bias in policing; there have also been numerous examples of student unrest at college campuses across the country, inspired by the racial bias and institutional indifference of college and university leadership; there has been the immigration debate especially heated in the lead up to the next presidential election; and there has been the ever-present threat of terrorism that has prompted some politicians to call for the curtailing of the rights of Muslims. And even as we saw the success in the movement for marriage equality bring previously unimaginable rights to gay and lesbian couples, this success has helped reveal the need for greater consideration of the conditions of the transgender community. All of these events and debates have come together in the last several years to bring the subject of race and identity politics from a discussion that had always taken place within diasporic and marginalized communities, to one at the center stage of the national dialogue.

The term “post-racial” emerged to describe this current conjuncture. With the distance of more than fifty years, Dr. Martin Luther King’s ideals have entered into the mainstream discourse and an overall acceptance of the need for racial equality has emerged. In 1962 a young Dr. King sat in a Birmingham jail and penned a now-iconic open letter in response to white Alabama clergymen who were critical of his civil disobedience. In the letter he wrote of being

Cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.[1]

Yet underlying anxieties remain between acknowledging progress, and simply being Pollyannaish. These tensions erupted over the last few years in Ferguson, Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, and many other places bear this out. As Ta’ Nehisi Coates pointed out, “America’s struggle is not to become post-racial but post-racist”.[2]

The same dynamic we see at the national level we also see played out in miniature in the art world itself, though with an important difference. Having seen on the national level that each instance of progress in terms of diversity and tolerance, also serves to throw into greater relief the continuation of other deeper racial and ethnic divisions, and underlines the distance we still have to travel to close those divisions. Similarly, in the visual arts we find, on the one hand, these incredible strides in increased diversity in group exhibitions, solo exhibitions, an increased prominence and attention given to the legacy of artists of color among museums and collectors. While on the other hand, we find the demographic makeup of the art world as a whole, particularly art audiences, art historians and the artists they choose to write about, over-represents the white population significantly. A recent study puts the group classified as core museum visitors at over 90% white. Against the backdrop of the changing demographics of the country as a whole, this presents us with a worrisome figure. This important difference, that it is not representative of the ethnic and racial makeup of the United States at large, should be kept in mind when discussing race and identity in the art world.

This demographic disparity might explain the outcome of at least one high-profile racial controversy from the last several years, indeed one of the few such controversies to elicit protest and spill out into a wider dialog. A race-baiting (intentional or otherwise) series of works by artist Joe Scanlan were included in the highly prestigious Whitney Biennial in 2014, drawing condemnation from a group also included in the biennial, the largely African American Yams Collective. Scanlan, a Princeton professor, had produced works using a persona he created of an African American artist from Georgia named Donelle Woolford. The “artist” was performed by two African American actresses who made public appearances and performance as the nominal creator of the work in place of Scanlan. Many saw the ventriloquizing of black identity by a white artist as an expression of white privilege, and the inclusion of Scanlan caused further insult when critics pointed out that of the more than a hundred artists selected for the Whitney Biennial, 79% were white. The Yams Collective eventually withdrew in protest, in the face of administrative indifference.

The indifference of the Whitney leadership to the concerns of the Yams Collective and their supporters comes in contrast to the student protests against discrimination that have taken place on numerous college campuses this past year. Minority students’ in these campuses, from University of Missouri to Claremont to Yale, who sensed being subject to subtle (and not-so-subtle) forms of discrimination, brought their concerns to administrators. When their concerns were brushed aside by college administrators, the country witnessed waves of protest in response that forced the colleges to act. The protests of the Whitney’s inclusion of Scanlan never gained enough momentum to elicit an official response from the museum. In light of what unfolded at so many college campuses, had the core audience of the museum been more than 9% nonwhite, we can imagine the possibility of a different outcome where a more diverse base would more readily identify with the concerns of the protestors.

Of course it would be wrong not to acknowledge that there has been the belated institutional discovery of historically important artists like Norman Lewis, alongside the commercial success of great contemporary artists like David Hammons, Wangetchi Mutu, El Anatsui and others. In the last year we have seen exhibitions in Los Angeles of Noah Purifoy at LACMA, William Pope.L at MOCA and Charles Gaines at the Hammer Museum. In New York, even the retrograde Whitney Museum featured a solo exhibition of Archibald Motley, and throughout New York there was Martin Wong at the Bronx Museum, On Kawara at the Guggenheim, a historical survey of Latin American Modernism at MOMA. These institutions are still evolving on the matter of diversity. While rotating exhibition spaces are broadening their scope, permanent collections and what is permanently on view take many more years to rebalance.

The premise of SKIN is that these conversations have been ongoing amongst artists and through art production itself, and one of the aims of this exhibition is to begin to connect the various conversations to one another and to bring the discussion into a central discursive space. The exhibition includes work that addresses these issues in many ways, from the most topical to the theoretical. Artists such as Maura Brewer, Holly Crawford, Nery Gabriel Lemus, Cole M. James, Gabriel Sosa, Farrah Karapetian, Derrick Maddox, Daniel Rothman, Sandy Rodriguez, Zeal Harris, Bruce Richards hew to the latter, informed by lived experience, current events, and topical political concerns.

Cole M. James’ work for example, was produced after the artist’s bracing visit to Ferguson, Missouri during the Michael Brown protests, at the invitation of Amnesty International. Sandy Rodriguez’s work also takes the Ferguson protests and the militarized police response as its subject matter in a series of paintings. Ferguson is the now-infamous location of the incident in which an unarmed African American, Michael Brown, was shot and killed by white police officer Darren Wilson. Massive demonstrations erupted following the tragedy, as the incident was seen as symptomatic of institutional racial bias in policing. The protests quickly went national, and galvanized the already nascent Black Lives Matter Movement towards a wider struggle for police reform.

The attempts to depict, or viscerally capture the emotion of this violent event and its aftermath run the risk of glorifying trauma, and aestheticizing political struggle. An exhibition in Chicago ran straight into these pitfalls. Taking place at Gallery Guichard, artist Ti-Rock Moore created a disturbingly realistic replica of the slain body of Michael Brown lying face down in his own blood. Another example, artist and “conceptual poet” Kenneth Goldsmith presented a reading of Michael Brown’s autopsy report as if it were Goldsmith’s own poetic text. Potentially, works like these can arouse strong sympathy in the viewer, but this sympathy can absolve the audience of further responsibility. As if to say, “I care, and by caring I have done my part.” Still, more darkly, these works can merely reproduce trauma, and revictimize already victimized communities. In light of these events, we have included interactive educational nodes in the exhibition. Node 3 invites our audience to reflect on their city and neighborhood and offer comments on what makes their neighborhood thrive and sustainable.

Cole M. James and Sandy Rodriguez avoid sensationalizing events by creating works that instead ask questions and begin a process of further investigation and production. Rodriguez is producing an ongoing series of nocturnes in oil. At only 16 by 20 inches in size, the vibrant yellows blues and oranges of her series burst and bloom against a murky black background, like the sublime atmospherics of J.M.W Turner, the British Romantic landscape painter. However these works capture light effects that were produced artificially by urban lighting and signage, and filtered through teargas. In James’ work, her experience led her to look at Ferguson indirectly, and instead ask the structural question, “How is racism perpetuated with recognition and prevention?” Her work Love Flesh Rot looks at the racial assumptions embedded in everyday language and points to the need for, and difficulty, in adequate communication.

Like James, several artists in the exhibition share an interest in the role language plays in reproducing racial hierarchies, such as Kathie Foley-Meyer, Margaret Noble, Larissa Nickels, and April Bey. Bey, for example, creates a pseudo-scientific African American skin-tone spectrum, and a corresponding spectrum of character labels that grow incrementally more positive as the skin tone they relate to grows lighter, highlighting the arbitrariness of each distinction. Similarly, Jessica Wimbley’s collage-like compositions explore the complex intersections of culture, history, and biography at play in identity formation.

Ken Gonzales-Day also explores the systematizing of knowledge. His 41 Objects Arranged by Color combines objects that were photographed in eleven different museum collections in order to consider the depiction of “skin” across time. Gonzales-Day writes that:

The piece is meant to speak to the sometimes arbitrary nature of historical attempts to represent human difference in both the fine arts and in the sciences. This piece includes objects and collections that reflected, and contributed to, modern racial formation in the West. The idealization of the whiteness can be found in Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave, 1851, and in a French mannikin from the 1930s, while life-casts of Native Americans and Africans could be depicted in everything from shimmering gold to metallic green patinas and point to the sometimes fantastical representation of the Other in Western culture.

Gonzales-Day’s piece, photographing examples from across the globe, and from across the history of art puts into perspective the reductiveness of the simple racial binaries that circulate in contemporary American political discourse.

Another major issue relating to identity circulating in political discourse during the Obama presidency is the immigration debate, including the considerable political capital he has spent on an unsuccessful attempt to pass comprehensive immigration reform. Several artists in SKIN explore the subject, not as political position-takers, but as individuals embodied in the experience, and who attempt to convey the phenomenology of dislocation often felt by immigrants. These artists include Ann Le, Camella DaEun Kim and Nery Gabriel Lemus. SKIN includes selections from Lemus series of large-scale drawings on paper that allegorically explore the solidarity between Latinos and African Americans through the characters Corky, a brown bear, and Bunchy, a black panther. Through his series, Lemus connects these communities that are in balkanized political discourse as separate, even at odds with each other, but Lemus links these communities into a common narrative, in a way that SKIN, the exhibition as a whole, aims to do.

Intersecting narratives between communities can also be seen in work of Duane Paul. The rapid success of the movement for marriage equality and a growing presence and acceptance of gay and lesbian individuals in mainstream institutions has allowed focus to shift to inequalities within the LGBT community itself. The transgender community for one, has seen increased attention paid to their particular issues and concerns. In Paul’s work we see another facet of the LGBT community: the role that race plays in the community, through a series of diptychs and triptychs photographs. Works from this series included in SKIN are Dancing Gets Me Noticed and Myth of the Lockness Cock. They consist of ambiguous self-portraits made through layering the visual field with stretched rubber, Paul’s work explores the unacknowledged racial undertones of gay male desire.

In addition to topical subjects, artists in SKIN engage in concerns both theoretical and historical, such as Maura Brewer, Christopher Christion, Malisa Humphrey, and Kara Walker. Christopher Christion for example is concerned with the workings of power itself, while Maura Brewer in Zero Dark Birthday examines the racial politics and unstable boundaries between self and other through a re-edit and intervention into the footage of the film Zero Dark Thirty, a typical Hollywood studio production.

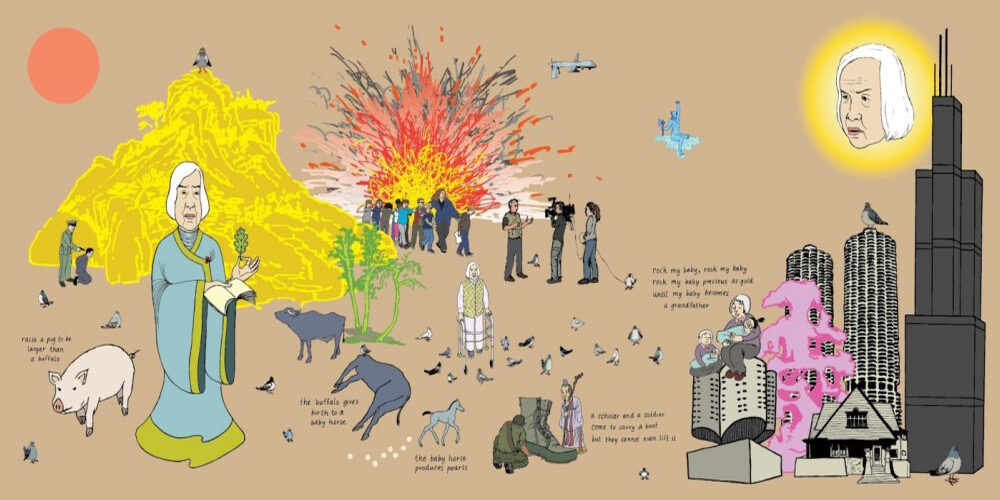

The exhibition aims for a balance between the critical and the utopian. Artists who give a momentary glimpse of a horizon of new possibility such as Fabian Debora through his pedagogy targeted towards Homeboy Industries students, and Cauleen Smith through a video work documenting a high school marching band playing a composition by Free Jazz pioneer Sun Ra through public space. The work, titled Solar Flare Arkestral Marching Band: Rich South High School to Chinatown Square, takes the normally regimental high school band and everything that it implies in terms of football and local pride, and moves it into an unfamiliar (and unsuspecting) cultural context. The typically regimented style of music of the marching band repertoire is replaced with Sun Ra’s epic outer-space jazz Afrofuturism. The meaning of public space and what is possible expand beautifully.

Since the inception of the United States of America, issues surrounding race and identity have played an important role in how Americans see themselves. As Jeff Chang writes “[Race] is about what we see and what we think we see and what we think about when we see.”[3] Over the centuries, the identity of those who could be ‘seen’ was filtered by race, economics and power. As President Obama pointed out in an interview in late 2015 “It was a debate that took place when…there were signs on the doors saying ‘No Irish need apply.’ It was a debate that happened during Japanese internment in World War II. It was obviously a debate in the South for most of our history and during the civil rights movement. And it’s been a debate that we’ve been having around issues of the LGBT community…”[4] As we struggle to understand each other, the importance to be heard as well as to be listened to is pivotal. How we respond to this challenge will become the legacy we pass down across the generations.

In placing SKIN at the center of the conversation, the gallery aims not to answer questions or make sweeping conclusions about where we are, but to create a space where more questions and more dialogue can take place. It is through conversations with each other, not mediated via social media, that the gallery hopes to support conversations that are both thoughtful and thought provoking. SKIN hopes to achieve this through interactive educational nodes, performance, workshops, discussions.

[1] King, Martin Luther, Jr. Letter From Birmingham Jail. N.p.: Great Neck, 2009. Letter from Birmingham Jail. USC Rossier School, June 2012. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[2] Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “There Is No Post-Racial America.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 22 June 2015. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

[3] Jeff Chang, Who We Be : The Colorization of America (New York : St. Martin’s Press, 2014), 2.

[4] Interview by Steve Inskeep. Video And Transcript: NPR’s Interview With President Obama. National Public Radio, 21 Dec. 2015. Web. 26 Dec. 2015. <http://www.npr.org/2015/12/21/460030344/video-and-transcript-nprs-interview-with-president-obama>.